Sunday, March 1, 2009

TheLaw.net Equalizer User Manual

2. Overview & Coverage

3. Build Your Search

4. Analyze Your Results

5. Review The Opinion

6. Search Methods and Syntax

---Advanced Search By Statute

---A Murder In North Dakota

---Advanced Search Techniques

---No Word Guessing!

7. Find Unknown Opinions

8. Citation Lookup

9. Introducing Citetrak

10. Validate Your Research

11. Dual Column Printing

12. Citation Guide

13. Linkbar Menu System

14. Miscellaneous Tips & Tricks

15. TheLaw.net Virtual Assistant

16. Troubleshooting

17. Subscription Management

18. Contact Information

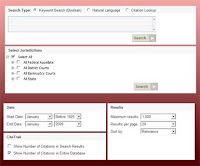

03. BUILD YOUR SEARCH

FEDERAL DISTRICTS (1 F.Supp. 1 To Date) To search all United States District Courts, deselect "Select All" by clicking the "Select All Checkbox." Then, click the checkbox captioned "All District Courts." To isolate one or more Federal districts click the plus symbol just to left of the "All District Courts." This expands the menu as pictured in the graphic below. Click the checkbox(es) that corrspond with the jurisdictions you want to search.

BANKRUPTCY (1 B.R. 1 To Date) To search all United States Bankruptcy Courts, deselect "Select All" by clicking the "Select All Checkbox." Then, click the checkbox captioned "All Bankruptcy Courts." To isolate one or more bankruptcy jurisdictions, click the plus symbol just to left of the "All Bankruptcy Courts." This expands the menu as pictured in the graphic below. Click the checkbox(es) that corrspond with the jurisdictions you want to search.

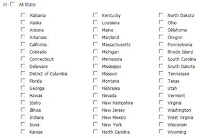

STATE COURTS & D.C. (1950 To Date) To search all state courts, deselect "Select All" by clicking the "Select All Checkbox." Then, click the checkbox captioned "All State." To isolate one or more states click the plus symbol just to left of the "All State Checkbox." This expands the menu as pictured in the graphic below. Click the checkbox(es) that corrspond with the jurisdictions you want to search.

You can also cherry pick any combination of jurisdictions from each category. If you're in New York and you want to perform a comprehensive, true primary jurisdiction search you can click New York State, then add the Eastern, Western, Southern and Northern Bankruptcy and District Courts, then add the Second Circuit and United States Supreme Court. One mouseclick searches all of the selected jurisdictions simultaneously. Click here, for even more useful information on searching for known opinions from this original search screen.

Sunday, February 8, 2009

Adjust Text Size

It says:

File Edit View Favorites Preferences

From the VIEW MENU select TEXT SIZE

No Word Guessing!

To an extent they are right. In the absence of a toolset of best practices legal researchers guess words.

Here's the question? Why guess words when the text and/or number of your controlling statute, rule, regulation or judicial opinion forces your choice of words.

782.04 is the number assigned by the Florida legislature to the first degree murder statute in that jurisdiction. If we want to check first degree murder cases in Florida, we anchor our query with this number. Not only do we find every first degree murder case citing our statue, that's all we find because with such a unique search term, it's impossible to find anything but first degree murder cases.

The gatekeepers of legal research love to say, "You never know where you might find the answer." This is crap!

Of course we know. We're going to find our answer in a judicial opinion that construes our controlling codified item(s) of information or concept(s) for the reason(s) we care about. Or not. But we're going to resolve the search to 'yes' or 'no' in a click or two. Guided by the strict language of the law, we find what's there, what's not there and move on.

782.04 & "sexual battery" finds the subset of Florida first degree murder cases where the separate felony of sexual battery is involved. Had we been guessing words, our query would have been poisoned by the addition of the term 'sexual assault', for example. But, we were not guessing. 'Sexual battery' was cribbed directly from the plain language of 782.04. Our additional search term choice was forced by the statutory language.

Throughout our search, we consistently invoke the language of the law. We never step outside the four squares of terms chosen by legislators, regulators, rulemakers or judges. Unless the facts of our case force an alternative or additional choice of words.

Perhaps the murder weapon is a knife.

782.04 & "sexual battery" & (knife or stab!)

This search finds opinions citing our statute in a sexual battery context, together with knife or derivatives of stab, i.e. stab, stabbed, stabbing. Our alternative 'or' terms are grouped in parenthesis. As a Boolean searcher, this is the only time you use parenthesis.

Anchor your query with the number assigned to the controlling codified item of information driving your search. If necessary, filter these results by leveraging the unique nomenclature provided in the text of the controlling law, regulation or rule. Never - ever - guess words.

Thursday, February 5, 2009

Mission Statement

TheLaw.net would make a great Harvard Business School course on how to grow a sustainable start-up from cashflow. The company has been cash positive since Day One - a success by any objective measure. That said, our biggest challenge has been fighting computer illiteracy.

Legal researchers use the computer differently and badly. That’s why in December of 2008, I decided to start this blog, Legal Research Best Practices. For your information, before I started this blog, the phrase legal research best practices did not appear in an advanced search of Google's index.

I have a populist attitude when it comes to American law. I don’t believe it should be the commodity it has become. I don’t think we should have to go to multi-billion dollar, offshore monoliths like Thomson-Reuters and Reed Elsevier so we can rent databases comprised primarily of information originally paid for by American taxpayers.

The philosophy behind TheLaw.net Corporation is that for a relatively nominal cost, everyone gets to see everything. Thereafter, everyone makes their best argument and may the smartest lawyer win. Go ahead. Call me an idealist. I take it as a compliment.

The original purpose of this blog was to teach individuals how to use the computer to supercharge their search results. In other words, I wanted to teach legal researchers how to do an end-run around all of these annotations, headnotes and key numbers the gatekeepers of legal research - most of whom have never appeared in court - contend represents the Gold Standard.

I wanted to show folks how to replicate the results they receive using these various casefinders, in just a click or two on the computer. Here’s what happened to that idea.

In the course of comparing my results to the resources provided by West attorney-editors I discovered a lot of missing annotations. For instance, I conducted a study of jurisprudence related to the Federal wire fraud statute – 18 U.S.C. § 1343 - the details of which are published here.

West's 1343 Annotated lists approximately 1,000 headnotes in the so-called Notes Of Decisions. Many of these headnotes cite the same opinion for different reasons. Others cite the same opinion for the same reason, but appear in more than one 1343-related category. Accordingly, 1343 Annotated cites to less than 1,000 unique opinions. That’s bad news for West because according to my research, we have more than 3,000 Federal judicial opinions that construe this statute.

Where are the notes regarding the other 2,000 opinions?

West says its annotations are complete, that everything is all in one place and that all you have to do to ensure you don’t miss any important law is become a subscriber. I wonder if this is an aberration? Maybe the attorney-editor assigned to 1343 graduated last in law school, still lives at home with his mother in Eagan, Minnesota and his pocket-protector recently sprang a leak. Who knows?

About a week ago, I'm talking to our intellectual property counsel about this issue. In advance of our meeting and with him in mind, I pull the annotations to 17 U.S.C. § 107. Then I run a national search using TheLaw.net Equalizer 7.0. My results are pre-sorted by Relevance - a term of art meaning search term frequency.

My query is: 17 /5 107 & "fair use" which asks for opinions where the section number appears within five words of the title number, together with at least one appearance of the phrase fair use someplace in the document.

I receive several hundred hits from Federal appellate and district reported opinions. My top 10 reported hits are:

1. 227 F.3d 1110

2. 478 F.Supp.2d 607

3. 203 F.3d 596

4. 211 F.3d 21

5. 142 F.3d 194

6. 523 U.S. 135

7. 862 F.Supp. 1044

8. 847 F.Supp. 142

9. 214 F.3d 1022

10. 37 F.3d 881

Hit No. 1 is noted twice in 107 Annotated.

Hit No. 7 is noted six times.

Hit No. 8 is noted 13 times.

Hit No. 9 is noted once.

Hit No. 10 is noted once.

Hits Nos. 2 thru 6 are not noted in 107 Annotated, even though six of the fourteen headnotes created by West's attorney-editors for Hit No. 3 – 203 F.3d 596 – expressly cite and link to section 107.

Similarly, 17 of the 19 headnotes created by West attorney-editors in connection with Hit No. 5 – 142 F.3d 194 – expressly cite and link to section 107. How does this case not make it into 107 Annotated? Do the headnote people not talk to the annotation people?

Hit No. 6 – Quality King Distributors v. L'anza Research, 523 U.S. 135, 118 S.Ct. 1125, 140 L.Ed.2d 254 (1998) – contains the following language: "The 'fair use' defense embodied in § 107 FN22 would be unavailable to importers if § 602(a) created a separate right not subject to the limitations on the § 106(3) distribution right....In the context of this case, involving copyrighted labels, it seems unlikely that an importer could defend an infringement as a “fair use” of the label. In construing the statute, however, we must remember that its principal purpose was to promote the progress of the “useful Arts,” U.S.Const., Art. I, § 8, cl. 8, by rewarding creativity, and its principal function is the protection of original works, rather than ordinary commercial products that use copyrighted material as a marketing aid. It is therefore appropriate to take into account the impact of the denial of the fair use defense for the importer of foreign publications. As applied to such publications, L'anza's construction of § 602 “would merely inhibit access to ideas without any countervailing benefit.'”

The foregoing United States Supreme Court opinion is not noted in 107 Annotated.

In light of this pattern, the Mission of this blog is to show you how to quickly find the opinions opposing counsel has been missing as a result of reliance on West's manmade casefinders.

Before the computer there was no way to know what you were missing browsing annotations. Before the computer, if you missed important law, opposing counsel missed it, too. You both used the same key numbers, annotations and headnotes to locate any potentially relevant opinions.

Today we can compare results and the upshot is that the index of judicial opinions created by the computer is complete. Indexes and pathfinders created by attorney-editors, by definition, are partial. Complete beats partial every time. But, only if you have a set of best practices in place to ensure you are finding everything you need and nothing you don't need in a couple of mouseclicks.

This blog is intended to ensure - regardless of whether you use West, Lexis or TheLaw.net - that you will know how to find what you need quickly, easily and with confidence. The advanced search techniques set forth herein will keep you from wasting hours browsing headnotes, annotations and key numbers.

You will have more in less time without missing cases, making you the smartest lawyer in the room and a force to be reckoned with!

Wednesday, February 4, 2009

Tutorial: Advanced Search Techniques

About "Advanced." "Advanced" doesn't mean difficult. "Advanced" is a computer-related term of art that means "no one does it!"

You're a lawyer. You can tell me whether principles of collateral estoppel and res judicata apply in jurisdictional questions. Accordingly, I know you separate the two words with an ampersand and click Search! So, let's do this.

The sample searches in this tutorial are anchored to and driven by the Florida first degree murder statute. Watch how we build our individualized search path. First we find all opinions citing our statute. Next, we find all opinions citing our statute for the reason we care about. Then, using Equalizer's results analysis tools we pinpoint the leading case from among our results. Thereafter, we look for cases citing that case for the reason(s) we specify.

Accordingly, our search pivots. It goes from being all about the statute, to being all about our case. Along the way, we filter using terms provided by the text of the statute. That way we are sure to speak in the language of the law, avoiding the diffuse, ambiguous results and information overload that comes from word guessing.

If you decide to practice these searches, run them only in the Florida state database. If you don't know how to isolate only the Florida state database, click here.

1) Lookup A Known Opinion

Instructions: All you need is volume and starting page.

Sample Search: Enter 792 P.2d 801 and click SEARCH

Results: Your opinion pops up.

2) Lookup More Than One Known Opinion Simultaneously

Instructions: To lookup multiple opinions in a single search separate each citation with a comma.

Sample Search: Enter 792 P.2d 801, 375 So.2d 836 and click SEARCH

Results: Both opinions pop up.

3) Find Any Opinions Citing Your Statute*

Instructions: To find opinions citing the codified item of information driving your search, simply enter the number. In Florida, for example, when we search on murder or homicide we receive in excess of 10,000 opinions containing at least one reference to one of our search terms.

Sample Search: Check the Florida State Database, enter 782.04 and click SEARCH

Results: On this date we find 998 Florida state opinions that expressly cite the Florida first degree murder statute.

4) Find Any Opinions Citing More Than One Statute

Instructions: To find opinions citing more than one statute, enter your two statute numbers separated by &.

Sample Search: Enter 782.04 & 782.02 and click SEARCH

Results: On this date we find 16 Florida state opinions that expressly cite the Florida first degree murder statute, together with the justifiable homicide statute.

5) Find Any Opinions Citing A Word

Sample Search: Enter murder and click SEARCH

6) Find Any Opinions Citing More Than One Word

Instructions: To find opinions citing more than one search term anywhere in the text of the case, separate the terms with AND or the 'and' symbol - &

Sample Search: Enter murder & homicide and click SEARCH

Results: Opinions containing at least one reference to each term pop up.

7) Find Any Opinions Citing A Phrase

Instructions: Use quotations marks to find opinions containing a specific phrase.

Sample Search: Enter "sexual battery" and click SEARCH

Results: Opinions containing at least one reference to your phrase pop up.

8) Find Opinions Citing More Than One Phrase

Instructions: To find opinions citing more than one search term anywhere in the text of the case, separate the terms with AND or the and symbol - &

Sample Search: Enter "first degree murder" & "sexual battery" and click SEARCH

Results: Opinions containing at least one reference to each phrase pop up.

9) Find Opinions Including Alternative Number(s)/Word(s)/Phrase(s)

Instructions: To find opinions containing alternative search terms anywhere in the text of the case, separate the terms with OR.

Sample Search: Enter "sexual battery" or "sexual assault" and click SEARCH

Results: Opinions containing at least one reference to one phrase pop up.

10) Find Any Opinions Citing Part Of A Word(s)/Phrase(s)

Instructions: To truncate or to find derivative terms use an asterisk ( * ) or exclamation mark ( ! ).

Sample Search: Enter employ* and click SEARCH

Results: This search finds opinions containing employ, employs, employed, employee, employment, etc.

11) Find The Opinion Citing Your Search Term(s) Most Often

Instructions: The column on the far left on your results screen is captioned Relevance. This is an abbreviated way of saying search term frequency. Relevance speaks to the substance of the conversation regarding your search criteria. Results are sorted by Relevance by default. The higher percentage ranking an opinion receives, the more relevant it is in relation to other opinions matching your search criteria.

12) Find The Most Recent Opinion Matching Your Search Criteria

Instructions: The column in the right half of your results screen is captioned Decision Date. To sort results by recency click the link captioned Decision Date. The most recent term to cite your case is not necessarily the most relevant. Appellate opinions typically resolves three to five questions of law. Your case may or may not be cited most often for your point of law. All this does is to provide you with the most recent opinion to match your search criteria regardless of search term frequency or citation frequency.

13) Find The Most Cited Opinion Matching Your Search Criteria

Instructions: The column on the far right of your screen is captioned Citetrak Entire Database. Viewed vertically, a series of numeric hyperlink appear. Each numeric hyperlink tells you in the first instance, whether an opinion has been cited. More than half of all published opinions have never been cited. Accordingly, more often than not the numeric hyperlink assigned to a given opinion in your results list will be zero ("0"). By default, the number assigned to each opinion tells you how many times it has been cited nationally. If you click the link you will see the cases. To sort by citation frequency, click the link captioned Entire Database. The most cited opinion matching your search criteria is now ranked first. Considering relevance together with citation frequency, will provide you with at-a-glance insight into opinions that are being cited most often for your point of law. A "most cited opinion" that has a 10% relevancy ranking is being cited primarily for point(s) of law that do not match yours. Conversely, a most cited opinion with a relevancy ranking of 90% is being cited most frequently for your point of law.

14) Find All Opinions Citing Your Statute For The Reason(s) You Specify

Instructions: Using the text of the statute as your guide, choose the word or phrase that's important to you and filter your results by adding said word or phrase to your search.

Sample Search: Enter 782.04 & "sexual battery" and click SEARCH

Results: This search finds any opinions citing your statute, together with additional search terms anywhere in the text of the case.

15) Find Any Opinions Citing A Number/Word/Phrase Together With At Least One Of Several Alternative Number(s)/Word(s)/Phrase(s)

Instructions: Using the facts of the case to force our choice of words, we filter by alternative terms, any instance of which would be relevant to our case.

Sample Search: Enter 782.04 & (knife or razor or stab!) and click SEARCH

Results: This search finds opinions citing your statute, together with at least one variation related to the cause of death.

Note: When searching for at least one occurrence of alternative terms together with at least one instance of a specific term, you must use parenthesis to group the alternative terms. It's like an algebra equation. This is also the only circumstances in which you would use parenthesis.

16) Find Any Opinions Citing A Number/Word/Phrase Within A Specified Number Of Words Away From Any Other Number/Word Phrase

Instructions: Find any cases citing to a specified Federal statute or regulation.

Sample Search: Enter 18 /5 1344 and click SEARCH

Results: This search asks for opinions where the section appears within 5 words of the title number. We could have entered, for example: "18 U.S.C. § 1344" or "18 U.S.C. sec. 1344" or "18 U.S.C. section 1344" or "18 U.S.C. §§ 1001, 1014, 1344". Why do all of that typing when 18 /5 1344 solves for every contingency in one mouseclick?

Note: This format also works if your primary practice jurisdiction originates in the states of Maine, Massachusetts, Vermont or otherwise, where the statutory format is Title Number/Jurisdiction/Section Number.

17) Find Any Opinions Citing Your Opinion

Instructions: Put quotation marks around your citation to turn it into a search phrase. This is called a citation driven search. You've been doing citation driven searches for years using the West and Lexis citators.

Sample Search: Enter "792 P.2d 801" and click SEARCH

Results: You find opinions citing your opinion in the jurisdictions you selected.

18) Find Any Opinions Citing Your Opinion For Your Point Of Law

Instructions: This search began with the Florida first degree murder statute - 782.04. Our search lead us to 997 opinions. Our search on 782.04 & "sexual battery" lead us to 145 opinions. The most cited/relevant of these 145 opinions is 375 So.2d 836. CiteTrak instantly tells us that this opinion has been cited 87 times. We know that appellate opinions typically resolve three, four or five points of law. When we started our search it was all about the statute. Now it's all about this judicial opinion. But, we only want the subset of 87 opinions that cite our case for our point of law.

Sample Search: Enter 375 So.2d 836 & "sexual battery" and click SEARCH

Results: Of the original 87 opinions citing our leading case, 23 of them also expressly reference the term "sexual battery." In the results we sort by recency (Decision Date) and learn that the most recent opinion (of the 23) to cite our opinion for our reason is: Brown v. State, 761 So.2d 1135 (Fla. App. 1 Dist. 2000)

Note: In seconds we went from the batch of 997 opinions citing our statute, to the subset of 145 opinions citing our statute for our point of law, to the subset of 23 opinions citing our most relevant opinion for our point of law, to the most recent opinion to cite our leading case for point of law. Not bad for a couple of minutes work.

----------

* - For purposes of this tutorial, the term "statute" means statute, rule or regulation. All are codified items of information, comprised of a unique set of numbers in a unique format. Always anchor your search with the number assigned to the item of information driving your search. Why? For the same reason 404(b) is a better search term than prejudicial.

Saturday, January 31, 2009

Mark Whitney

Welcome to Legal Research Best Practices! My relationship with personal computing began in 1984, when I purchased an IBM XT with 10 MB of memory. For $6,000 one could type and print a document and project mortgage payments. Good times.

Welcome to Legal Research Best Practices! My relationship with personal computing began in 1984, when I purchased an IBM XT with 10 MB of memory. For $6,000 one could type and print a document and project mortgage payments. Good times.But, it was the summer of 1995, when serial entrepreneur Jim Barksdale and University of Illinois student programmer Marc Andreessen, released Netscape v. 1, forever transforming the human exchange of information. In my opinion, the release of Netscape represents human history's single most empowering event for the individual.

I was a 35 year-old ace legal researcher and writer, earning a fine living primarily in high stakes Federal criminal litigation. I even developed my own set of best practices for finding opinions no one else could find.

I conducted the research, analysis and documentation that lead to a $400,000 malpractice judgment against F. Lee Bailey. I was the first to identify, research and document the jurisdiction problem that resulted in the reversal and dismissal of an $8,769,740 million judgment in Lyndonville Savings Bank v. Lussier, 211 F.3d 697 (2nd Cir. 2000). My research and writing lead to the announcement of a new rule of law pursuant to the 1984 Bail Reform Act, when a unanimous panel of the United States Court Of Appeals for the First Circuit declared that Federal criminal defendants may not be detained in prison pending resentencing de novo.

When Netscape was released I took a year off, spending some 80 hours a week in front of the computer. At the end of that year, I co-founded Advanced Internet Research Strategies (AIRS), a company that predates Google and is still in business today. I spent six months writing and honing the curriculum. Thereafter, I spent two years teaching corporate America how to force true results from public search engines like Alta Vista, HotBot and Yahoo.

Back then, when Microsoft, Netscape and IBM, wanted to know how to use the Internet as a competitive intelligence tool, I am the guy they called. For $10,000 I would spend a single business day with 20 researchers or less.

In addition to corporate training, I conducted public seminars in Marriott meeting rooms from coast-to-coast. Different city every day. $1,000 a seat for eight hours, generating upwards of $75,000 a day in speaking fees. Ultimately, 55,000 corporate researchers would participate in this curriculum.

The first body of information to migrate online was porn. The next was legal information, as Federal and state governmental instrumentalities began uploading cases, statutes, rules, regs, forms, executive agency and legislative information.

The public web is a great reference resource. In fact, during the weeks and months to come I will be sure to post several Google tutorials so you can find just what you want and only what you want in one mouse click.

That said, the public web will never be a tool for conducting real legal research because the case law posted here is not comprehensive, verifiable, accountable, citable, sortable or checkable.

On January 1, 1999, I began working full-time on the project that would evolve into TheLaw.net Corporation. TheLaw.net was then and is now, a boutique infomediary that delivers all American primary law - proprietary, searchable, sortable, citable and checkable - to your desktop for less than $50 a month.

On August 1, 2000, TheLaw.net started booking subscriptions. The company has been cash positive ever since. Now in our 11th year, our flagship application, TheLaw.net Equalizer 7.0, is considered America's No. 1 legal research value.

Like Netscape and Microsoft Internet Explorer, Equalizer is a tool that has forever changed the lives of the local practitioner in today's online law office. Game-changing in that the playing field has been forever leveled in terms of access to primary resources with a national scope. Game-changing in that Equalizer is the superior case law search engine on the market today.

The opportunity for small-medium research environments is that large institutional users are - well - too institutionalized to change the way they do business. Morover, what they've been doing all these years has worked for them. They cannot imagine they're missing anything. To them, the notion that they are somehow lagging behind and missing cases by performing book-like research on a computer screen is laughable.

Tens of thousands of attorneys from coast-to-coast have come to TheLaw.net from Westlaw and Lexis. They know how to find all of the opinions Westlaw users are missing browsing headnotes, annotations and key numbers. They know how to do this in a couple of mouse clicks.

The information on this blog is used as an interactive support tool for subscribers to TheLaw.net. However, the advanced search strategies, processes, and other information revealed herein will supercharge your search results regardless of whether you subscribe to Westlaw, Lexis or TheLaw.net.